“If you look at the four seasons, each season brings fruit. In summer, there’s fruit, in autumn, too. Winter brings different fruit and spring, too. No mother can fill her fridge with such a variety of fruit for her children. No mother can do as much for her children as God does for His creatures. You want to refuse all that? You want to give it all up? You want to give up the taste of cherries” – Dialogue from Taste of Cherry (1997)

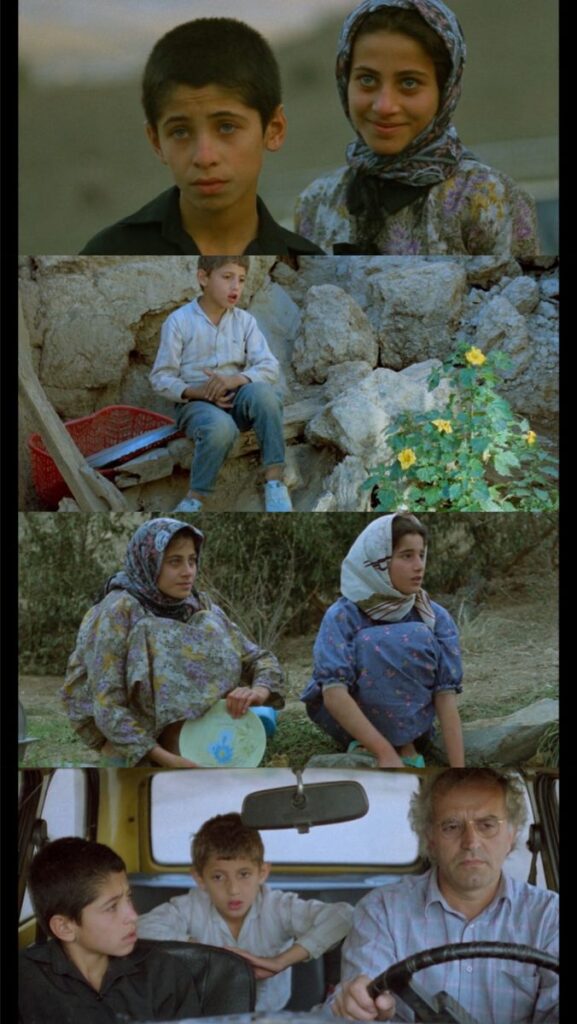

Such are the dialogues that enrich the voice of modern Iranian cinema. In the dried stillness of a post-revolution Iran, when voices were silenced and colors were stolen from the day today lives of the common people, the Iranian filmmakers found a new way to tell truths. They did it through the innocence of the children’s eyes, dusty roads, empty frames, and questions left unanswered. And did it exceptionally well. The poetic, humanist, metaphysical Iranian cinema emerged not with a great spectacle, but with the true spirit of being humane.

This is a cinema of resistance and transcendence. In the face of the censorship and restrictions, it painted the invisible with the indelible ink of courage. In a cinematic world that often demands plots and subplots, it dared to linger in silence.

The Origins: A Quick Peek into the History

In the 1960s and 1970s, Iran was going through massive shifts in it social and political arena. Mohammad Reza Shah, the last king of Iran, brought rapid urbanization, relative prosperity and educational development to the nation initiating a new era—full of intellectualism and artistic ambitions. This change, however, quickly brought on some dissatisfaction resulting in the Iranian Revolution of 1979.

The Iranian Revolution brought a seismic shift in cultural, political and social paradigms of the country. The monarchy perished, the Islamic Republic of Iran was established, drastically altering the trajectory of the nation.

It was during this time of profound transformation that Iranian filmmakers took a step forward to rediscover and rejuvenate the cultural identity of the country. This New Wave of Iranian film delved deep into the rich tapestry of Iranian history, traditions, and everyday life, reconnecting the people of Iran with the true spirit of the nation.

The origin of the Iranian New Wave goes back to the late 1960s. However, it reached its full poetic blossom after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Forough Farrokhzad’s haunting documentary The House Is Black (1963) and Dariush Mehrjui’s The Cow (1969) laid the foundation of this new wave, but Abbas Kiarostami, Mohsen Makhmalbaf and Jafar Panahi, and Asghar Farhadi are the real sculptors of its soul.

Although loved many times for its style, Iranian New Wave was really about survival. These filmmakers masterfully used allegory to survive censorship laws. Children became the protagonists, veiling critique in purity and innocence. These filmmakers used non-actors to give the movies a documentary-like feel. And the best feature? They let stories meander in the never-ending roads, refusing the Western love of resolution.

Cinema of the Real and the Sublime

The paradox the extraordinary in ordinary is what defines the Iranian New Wave cinema.

Abbas Kiarostami’s 1987 masterpiece “Where is the Friend’s House?” tells a story about a little boy trying to return his classmate’s notebook to save him from punishment in the class the next day. And that’s it; that’s what the movie is all about. Yet it is the minimalism of the story that gives it a deep moral and philosophical edge.

“Taste of Cherry” (1997) is another terrific film by Kiarostami. A man in a car searches for someone to bury him after his planned suicide. It’s a film where most of the drama lies in pauses, in beautiful village landscapes, in the unsaid words.

Iranian New Wave films often talk about death, ethics, memory, and existence. These simple films treat these themes without any magnificence. The camera observes quietly, never trying to intrude. It gazes with humility. Another magical trait of Iranian film is the eloquence that is prevalent in the ‘silence’ between the thoughts.

Poetry and aesthetics are other soul-stirring traits of Iranian films. These films bear brilliant reverberations of the ancient oral Persian storytellers and poets, especially Omar Khayyam.

The Metaphysical and the Meta-Cinematic

Iranian New Wave films frequently blur the line between reality and fiction.

Kiarostami’s “Close-Up” (1990) comes with this abundance. A man impersonates a famous filmmaker and travels through lives of real people. The real people play themselves, reenacting the events that destroyed their village. It’s not just a film about deception, rather a message about the longing to belong—to art, to dreams, to another self.

This recursive play between reality and illusion is central to the movement. It’s no surprise that Brechtian distance and meta-narrative layers find a home here, not as postmodern technique, but as ethical invitations to think, reflect, and feel.

Resistance and Repression

Despite international recognition and umpteen love from movie buffs, many Iranian filmmakers had to face the atrocities of the authority in many forms.

Jafar Panahi, known for The White Balloon (1995) and The Circle (2000), was famously banned from filmmaking. Yet he continued making films under house arrest. His film “This is Not a Film” (2011) was smuggled out of Iran in a USB drive hidden in a cake. This resilience cannot just be political, it is existential.

The Iranian New Wave proves that when freedom is denied, cinema finds a way through poetry, metaphor, children’s eyes, broken roads full of dust, and open endings.

Global Influence and Legacy of Iranian Films

The Iranian New Wave became inspiration to many filmmakers and cinephiles around the world. Kiarostami’s influence is prevalent in the works of Richard Linklater, Nuri Bilge Ceylan, and Kelly Reichardt.

To take the legacy one big step ahead, Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation (2011) won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

The Final Frame Zoom-In

The Iranian New Wave films are the quiet kinds. You’ll see the struggle of common people, the innocence of the children, you’ll feel the gentle afternoon wind brushing through the empty wheat fields. You’ll taste the silent moments between thoughts. You’ll become a part of the story. These films feel like exploration into the soul of people. There’s no male gaze or female gaze, but you will certainly gaze at the brilliance of filmmaking.

At Cinemagic Studio, we celebrate this movement not just as a chapter in film history, but as a way of seeing. A reminder that cinema, at its most honest, is not about what happens but how we see what happens.

If you loved what you’ve read, here’s a watchlist for you. You’ll find most of these movies on popular OTT platforms.

Where is the Friend’s House? (1987) – Abbas Kiarostami

The Wind Will Carry Us (1999) – Abbas Kiarostami

Taste of Cherry – Abbas Kiarostamin

The Cow (1969) – Dariush Mehrjui

The House is Black (1963) – Forough Farrokhzad

Close-Up (1990) – Abbas Kiarostami

The Mirror (1997) – Jafar Panahi

A Separation (2011) – Asghar Farhadi

No Bears (2022) – Jafar Panahi