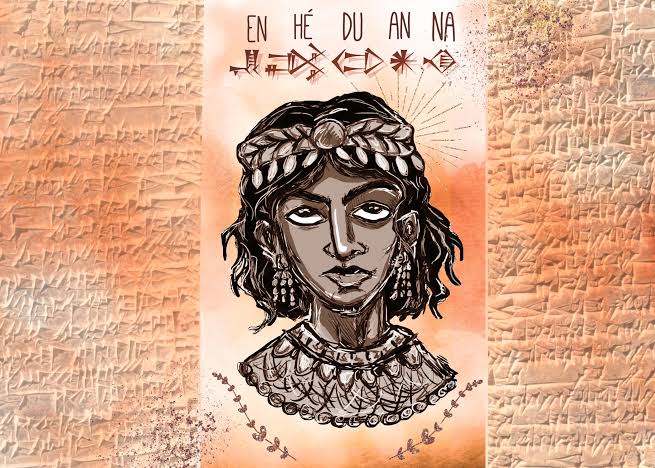

The Mesopotamian poet, priestess, and princess Enheduanna is considered as the first author and poet in all recorded history. Enheduanna was the daughter of Sargon of Akkad (Sargon the Great, r. 2334–2279 BCE), the king who built the first empire in history.

Enheduanna lived 1700 years before Sappho, 1500 years before Homer, and about 500 years before the biblical patriarch Abraham, which made her the first author in the practical sense. The name Enheduanna translates as ‘High Priestess of An’ (the sky god) or the ornament of heaven. Let’s know about her life and work in detail:

Enheduanna was born in Mesopotamia, the birthplace of the first cities and high cultures. Her father King Sargon the Great, conquered the independent city-states of Mesopotamia, the land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, under a unified banner. Sargon was a northern Sermite, who spoke Akkadian. However, the older Sumerian cities in the South were not impressed with him and treated him as a foreign invader. Frequent revolts erupted in these cities which became a threat to his newly conquered dynasty.

To bridge the gap between the rival cities and cultures, Sargon offered Enheduanna, his only daughter the position of the high priestess in the main temple of the empire. It was not a big step as female royalty was always serving religious roles. Enheduanna was educated, she could read and write in both Sumerian and Akkadian, and do mathematical calculations.

The city of Ur was home to 34000 people and had narrow streets, multi-storied brick homes, granaries, and irrigation. As the high priestess of Ur, Enheduanna managed grain storage for the city, led hundreds of temple workers, interpreted sacred dreams, and presided over the monthly new moon festival and rituals celebrating the equinoxes.

Enheduanna’s other aim was to unite the older Sumerian culture with the new Akkadian civilization. She composed 42 religious hymns combining both Sumerian and Akkadian mythologies as one of the ways to accomplish this goal of unification between the two cultures. In her time, each Mesopotamian city was ruled by a patron deity. Enheduanna dedicated her hymns to the ruling god of each major city. In her beautifully composed hymns, she praised the city’s temple, glorified the god’s attributes, and explained the god’s relationship to other deities within the pantheon. In her writing, she tried to humanize the gods in the shrines by depicting them as sufferers, warriors, and lovers and attentive to human pleading.

Writings of Enheduanna:

The earliest known writing was invented there around 3400 B.C. in an area called Sumer near the Persian Gulf. The development of a Sumerian script was influenced by local materials: clay for tablets and reeds for styluses (writing tools). At about the same time, or a little later, the Egyptians were inventing their own form of hieroglyphic writing.

The world’s first writing was invented in Sumer near the Persian Gulf around 3400 B.C. At that time, writing was used as a system of accounting, which enabled merchants to communicate with their long-distance traders. However, it was a pictogram system of record keeping that was not developed into a script until 300 years before Enheduanna’s birth. This early writing style was called cuneiform. It was written with a reed stylus pressed in soft clay tablets. But until Enheduanna, this writing method was used for record-keeping and transcription.

The best-known works of Enheduanna are Inninsagurra, Ninmesarra, and Inninmehusa translated as ‘The Great-Hearted Mistress’, The Exaltation of Inanna’, and ‘Goddess of the Fearsome Powers’. All of these hymns were dedicated to Inanna, the goddess of war and desire, the divine and chaotic energy that brightens up the universe. Inanna delighted in all forms of sexual expression and was considered so powerful that she transcended gender boundaries.

For Enheduanna Inanna was the most powerful of all deities. It was the first time in writing history the pronoun ‘I’ was used to explore deep and innate emotions of the human heart.

In “The Great-Hearted Mistress” (sometimes translated simply as A Hymn to Inanna), the poet writes:

“You are magnificent, your name is praised, you alone are magnificent!

My lady…I am yours! This will always be so! May your heart be soothed towards me!

…

Your divinity is resplendent in the Land! My body has experienced your great punishment.

Lament, bitterness, sleeplessness, distress, separation…mercy, compassion, care,

Lenience and homage are yours, and to cause flooding, to open hard ground and to turn”

Darkness into light. (lines 218, 244–253)

Her poem “Lament on War” is a wonderful depiction of her talent for creating arresting images and dynamic meter to deliver the message in her own way. The translated version of the poem by Michael R. Birch begins,

“You hack down everything you see, War-God!

Rising on fearsome wings

You rush to destroy our land;

Raging like thunderstorms, howling like hurricanes,

Screaming like tempests,

Thundering, raging, ranting, drumming,

Whiplashing whirlwinds!

Men falter at your approaching footsteps.

Tortured dirges scream on your lyre of despair.”

Historian Stephen Bertman observes,

“The hymns provide us with the names of the major divinities the Mesopotamians worshipped and tell us where their chief temples were located [but] it is the prayers that teach us about humanity, for in prayers we encounter the hopes and fears of everyday mortal life.”

Even keeping aside the aesthetics, her works had a profound impact on Mesopotamian theology. Enheduanna, with her hymns and prayers, created a richer understanding of god and deities bringing them closer to people.

Legacy of Enheduanna

After the death of her father, King Sargon, a general took advantage of the power vacuum and staged a coup. As a powerful member of the ruling family, Enheduanna became a target, and the general exiled her from Ur. However, her nephew, the legendary Sumerian king Naram-Sin, ultimately crushed the uprising and restored his aunt as high priestess. After that, Enheduanna served as a high priestess for 40 years in the city of Ur. After her death, she became a minor deity, and her poetry was copied, studied, and performed throughout the empire for over 500 years. Her poems influenced the Hebrew Old Testament, the epics of Homer, and Christian hymns. Even today, Enheduanna’s legacy still prevails, in various translated versions and clay tablets that have escaped the test of time.