In the smoky cafés of post-war Paris, a cinematic rebellion was brewing. It was late 50s.

A group of cinephiles, film critics and writers decided they were done with polished, traditional studio productions and predictable plots. They introduced the term “Nouvelle Vague” for the first time in a magazine they were associated with–Cahiers du Cinema. They rejected the Tradition de qualité (“Tradition of Quality”) of mainstream French cinema. They picked up cameras, hit the streets, and started shooting life as it was: messy, beautiful, and unpredictable.

This was the birth of the French New Wave—or La Nouvelle Vague. And it changed the face of modern cinema forever.

The Mood: Raw, Romantic, Rebellious

French New Wave wasn’t just a film movement. It was an attitude that disrupted the French cinema forever.

The dialogues of the films were often improvised. Characters talked about nothing and everything. These films were shot in natural lighting in the open. These movies talked about common people, their feelings, and philosophy.

The filmmakers of this New Wave movement explored new approaches to editing, unconventional visual style like less lighting, and non-linear narrative. These movies also explored existential themes.

The Pioneers of the Movement

Most of the pioneers weren’t trained filmmakers. They were film critics who loved cinema so deeply, they wanted to break it apart and build something new out of the debris. Some of the most prominent pioneers of the New Wave movement include François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Agnes Varda, Claude Chabrol, Éric Rohmer, and Jacques Rivette.

Andre Bazin and Henri Langlois, founder and curator of the Cinémathèque Française, were the dual father figures of the movement. These were directors who believed in the auteur theory—the idea that a film reflects its director’s personal vision, just like a novel reflects its author.

Most Prominent Films of the ‘New Wave’

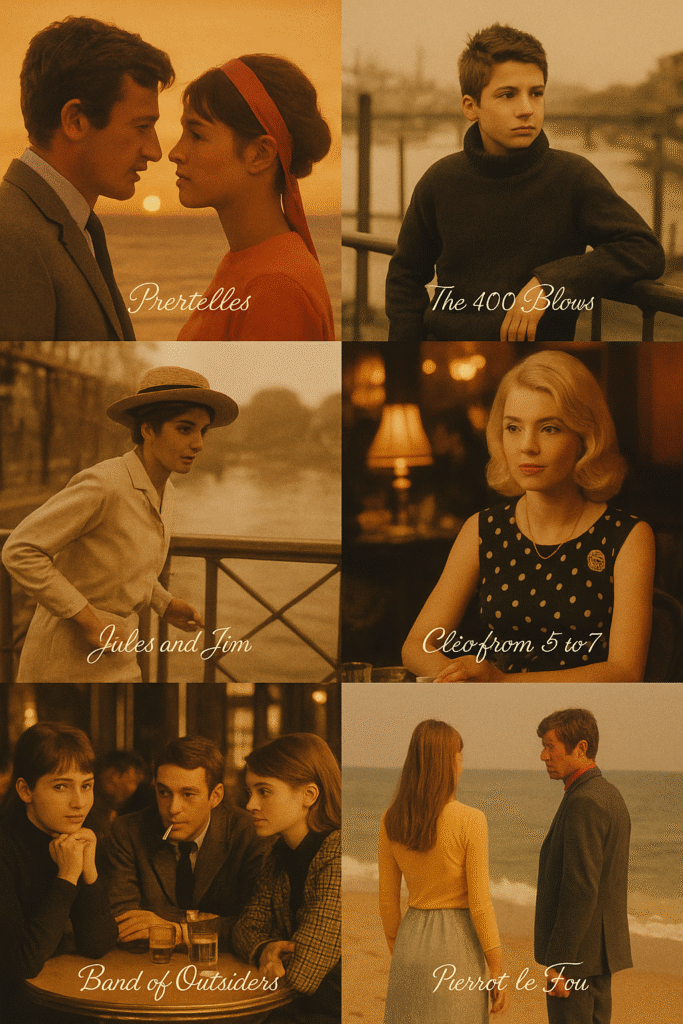

The French New Wave produced some of cinema’s most innovative and influential works. Here are a few standout titles that capture the movement’s spirit and legacy:

- The 400 Blows (François Truffaut, 1959)

A poignant, semi-autobiographical story of a misunderstood boy navigating a cold, indifferent world. It set the tone for the New Wave’s emotional depth and focus on youth, alienation, and rebellion. It’s a film that is perfect in all its endeavors. Stunningly beautiful, heartbreaking, liberating all the same time, this movie changed the landscape of French cinema.

- Breathless (Jean-Luc Godard, 1960)

Fast, fragmented, and effortlessly cool. This crime drama broke editing rules with its iconic jump cuts, reinventing cinematic rhythm and attitude. It felt like cinema redefining itself in real time.

- Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962, Agnès Varda)

A real-time journey through the streets of Paris as a woman awaits her medical results. It’s an introspective, feminist take on time, mortality, and self-perception—groundbreaking in its subtlety.

- Hiroshima mon amour (1959, Alain Resnais)

Blending past and present, memory and trauma, this film explores a fleeting relationship between a French actress and a Japanese architect. Emotionally complex and structurally innovative.

- Jules and Jim (1962, François Truffaut)

A love triangle set against the backdrop of war and shifting social norms. It’s lyrical, bittersweet, and full of the emotional freedom that defined the movement.

- Pierrot le Fou (1965, Jean-Luc Godard)

A visually striking road movie that mixes pop art, violence, romance, and political commentary. Visually rich and intellectually playful, it reflects Godard’s more radical side as he experiments with form, color, and narrative.

What Made the ‘Nouvelle Vague’ So Revolutionary?

The French New Wave wasn’t just about telling different stories. It was about changing how stories were told.

These filmmakers broke away from tradition. They used jump cuts to disrupt smooth editing and create a sense of spontaneity. Long takes were used to give scenes time to breathe, let emotions unfold naturally. Instead of expensive sets, they filmed on real locations, capturing life as it happened.

They used non-professional actors, improvised dialogue, and natural lighting, blurring the line between fiction and reality. The result? Films became personal, urgent, and raw.

But what really set them apart was the way they treated meaning. These films weren’t always about answers—they were about questions. About love, time, identity, memory. Sometimes abstract, sometimes intimate, but always thought-provoking.

Echoes in Today’s Cinema

The influence of the New Wave didn’t fade, it evolved.

You can see its influence all over modern cinema. Quentin Tarantino’s nonlinear storytelling owes much to Jean-Luc Godard. Richard Linklater’s character-driven, dialogue-heavy films echo the style of Éric Rohmer.

And the independent film movement? It lives in the spirit of the New Wave. Small budgets, creative freedom, and a focus on personal vision over polished spectacle make it so apparent.

Final Thoughts: The Wave That Never Ended

The French New Wave didn’t just leave its mark, it rewrote the language of cinema.

It reminded us that films like any other art forms don’t have to follow rules. That beauty can be found in the mundane. And storytelling is a deeply personal act, and it doesn’t require glitter and gloss to be appealing.

The credits roll here, but the story’s just beginning.

Subscribe to Cinemagic Studio for a front-row seat to film’s most poetic revolutions, forgotten frames, and appreciations of timeless classics.